Announcement for The Reformed Rumseller: Mr. Murphy, Wiscasset, 1872

Maine Historical Society

New Leaders

Between the Civil War and the end of World War I, the anti-liquor cause, now led by both reformers and Republican and Democratic politicians, built a power base on temperance success. Mainers contributed to this national reform through numerous leaders including Lillian M. N. Stevens, Francis Murphy, and the unsinkable General Neal Dow.

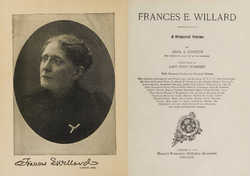

In this era, women became leaders of the fight against liquor. The most prominent prohibition organization, the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (W.C.T.U.), was founded in 1874. Though originating in Ohio, this countrywide group of politically activated women had strong roots in Maine. Lillian Stevens of Stroudwater was the right hand of President Frances Willard and succeeded her as national leader. Near the outset of the First World War, Mrs. Stevens was such a revered symbol of activist womanhood that she was honored by the lowering of the Statehouse flag at her death, the first woman so recognized. These tough-minded women engaged in other social causes including suffrage and aid to Armenian refugees and were part of an emerging generation of professional women.

During the 1870s, alcoholics including former Portland liquor-dealer Francis Murphy, Gardiner businessman J.K. Osgood, and Bangor physician Dr. Henry Reynolds were all instrumental in founding reform groups known for using red or blue ribbons as their symbols. Dr. Joseph E. Turner of Bath was one of the first medical authorities to describe alcoholism as a disease. In 1864, he opened America's first "inebriate asylum" in Binghamton, New York, to help cure its sufferers.

Prohibition on the Horizon

In Maine, liquor laws were gradually strengthened, and brewing, drinking, and selling were outlawed in the State Constitution in 1885. Even this step did little to dry up those who wished to imbibe. From 1905 to 1911, Maine created a Liquor Enforcement Commission with deputies empowered to arrest transgressing citizens. This limit on personal freedom proved exceptionally unpopular and the W.C.T.U. had to battle to save the Constitutional ban.

Opposition existed. Recent immigrants brought new drinking customs to the state and nation, as a way of preserving their native culture through traditional beer or wine making. College students continued to see social drinking as a rite of passage.

Near the end of her life in 1913, Mrs. Stevens told the faithful, "...we can see prohibition looming up all the way from Mt. Kineo in the east to Mt. Shasta in the west, from the pine forests in the north to the palmetto groves in the south. We verily believe that the amendment for national constitutional prohibition is destined to prevail and that by 1920 the United States flag will float over a nation redeemed from this home-destroying, heart-breaking curse of the liquor traffic."

If it was the Ohio-based Anti-Saloon League, founded in 1893, that eventually tipped the nation's voters into supporting Prohibition, it was the W.C.T.U., the ribbon reform movements, and other adherents who had created the critical mass. The citizens of the United States were about to embark on an experiment widely regarded as noble.